Dr. Anand Teltumbde wrote me:HI. Here is my column in current issue of EPW in case you like to see! Cheers!

My most respected friend and guide,the national professor who happens to be the grand son in law of Dr BR Ambedkar sent me his latest write up this Morning.

He wrote:

HI.

|

Annihilation of Caste!

WTO's Nairobi Ministerial by DR.Anand Teltumbde

Portents for Higher Education

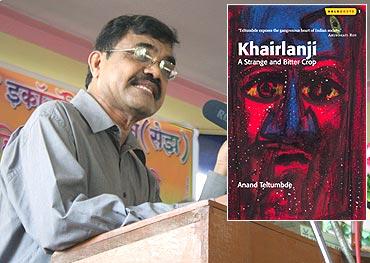

Anand Teltumbde (tanandraj@gmail.com) is a writer and civil rights activist with the Committee for the Protection of Democratic Rights, Mumbai.

At the 10th ministerial meeting of the World Trade Organization (WTO) to be held at Nairobi, Kenya, from 15–18 December, the discourse on higher education being public/merit/private good and the covert/overt preparation of the government over the past two decades to withdraw from higher education will finally come to an end. The conclusion of the current Doha round of negotiations, which started in 2001 but could not be completed because of the concerted resistance of the least developed and developing countries, has been planned for this meeting. A special meeting of the General Council of WTO was held in November 2014 at Geneva, which decided upon the process of suppression of resistance and finalised the "work programme" to conclude the negotiations in Nairobi. Once completed, it will have ruinous consequences for people in poor countries as variety of goods and services would suddenly be pushed beyond their reach.

For India, the consequences are not going to be any less severe. Its offer of market access in higher education made in August 2005 at Hong Kong will become an irrevocable commitment once the Doha round is concluded. While this offer was made by the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government, the current Bharatiya Janata Party-led National Democratic Alliance will pride on its consummation—again exposing the essentially anti-people character of these parties. The implications of this imminent disaster have yet not dawned on people commensurately despite a countrywide agitation under the aegis of the All India Forum for Right to Education (AIFRTE)—a federated body of hundreds of organisations and activists in the country, floated in 2009 to demand free and equitable education to all from kindergarten to post-graduation.

Spurious Economics

The protagonists of marketisation of higher education confuse people saying that higher education is not a public good. Public good in economics is narrowly determined on dual criteria: non-rivalrous and non-excludable, meaning one person's use of the good does not diminish another person's use of it and no person can be prevented from using the good, respectively. Placing public goods in the market defeats this dual criteria. Therefore, such goods are supposed to be provided by non-profit organisations and government. Classically, lighthouses and national defence exemplify public goods in economics. However, economics also notes that such examples are scarce in practice and most goods fulfil one criterion or the other, or sometimes are public goods and sometimes not. Often it is public perspective that makes a good public or private. For example, an official portrait of Henry VIII in the National Portrait Gallery in London is seen as a public good, but the painting of Mona Lisa in the Louvre is not. Many an item or service classically considered public good has been deftly turned into private good and brought in the realm of market—for example, the conversion of public roads to toll roads in recent times.

Why speak about higher education? Even the elementary education and primary health services can be termed as private goods with this argument. It is a pure neo-liberal ploy to commodify everything, including water and air, to be marketed for profits. In the public perspective, education in general, and higher education in particular, fulfils four major functions: the development of new knowledge (the research function), the training of highly qualified personnel (the teaching function), the provision of services to society (the service function), and social criticism (the ethical function). If we consider each of these functions, from even the economic criteria of non-rivalrous and non-excludability, higher education will lean heavily towards being a public good than a private good. For instance, the new knowledge is built upon the old knowledge; Einstein's theories would not be possible without the Newtonian base. The motivational argument given for restricting research as private good through intellectual property rights (IPRs) by the neo-liberalists is myopic. In the long run, the non-generation of theoretical knowledge or its confinement to elite networks through artificial devices like IPRs or other WTO mechanisms is bound to adversely affect the pace of new knowledge production—and thereby human future.

Then there is a perennial argument—from Macaulay's times—about the lack of resources for education. The National Knowledge Commission has predicted that India needs an investment of about $190 billion to achieve the target of 30% Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) in higher education by 2020 and expectedly advised to meet it through foreign direct investment (FDI) as the government lacks resources. For just one year, 2012–13, the tax revenue foregone by the government to companies worked out to Rs 5,73,627 crore (in excess of $100 billion by then exchange rate). Government has been gifting such amounts every year to corporate sector, the sum of which even for a few years would be in multiples of this requirement!

Huge Profit Potential

These arguments are just a cover for the naked interests of the global capital in the largest market of higher education in the world with over 234 million individuals in the 15–24 age groups, equal to the US population (FICCI 2011). This market of over $65 billion a year, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of over 18%, comprises 59.7% of the largely price-inelastic education market. It is rightly considered as the "sunrise sector" for investment. India's online education market alone, in which the US has evinced huge interests, is expected to touch $40 billion by 2017. An RNCOS (a market research firm) report, "Booming Distance Education Market Outlook 2018," expects the distance education market in India to grow at a CAGR of around 34% during 2013–14 to 2017–18.

The preparation for handing over this sector has been afoot right since 1986, when the New Education Policy allowed private investment into higher education, leading to mushrooming of private shops in the garb of educational institutes selling much-demanded professional education. They have since grown into veritable empires. After formally embracing neo-liberal reforms in 1991, there have been concerted attempts through committee after committee. These attempts culminated information of the Mukesh Ambani–Kumar Mangalam Birla Committee that created "A Policy Framework for Reforms in Education" in April 2000 to stress that higher education be left to market forces. Although the government has since scaled up self-financing through substantial raise in fees, it was not politically feasible to completely dismantle state financing of higher education. These moves, however, certainly prepared grounds for the offer of higher education to WTO in 2005.

UPA II had tried to clear all hurdles in committing higher education to the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) through various (six) bills, including the Higher Education and Research Bill, which advocated complete abolition of bodies such as University Grants Commission, Medical Council of India, All India Council for Technical Education and National Council for Teacher Education. The government, however, failed to get these bills passed in Rajya Sabha. Then the government resorted to its pet ploy of bypassing Parliament in launching a Rashtriya Uchchatar Shiksha Abhiyan (RUSA) in September 2013, to change the structure of higher education, undermining UGC and promoting public–private partnership (PPP). Choice-based credit system and common syllabus were some of the initiatives to facilitate prospective foreign players.

Successive governments adopted a competitive strategy in improving statistics of higher education and in the process winked at its rapidly falling standards. Even the few markers of quality education in India, Indian Institutes of Technology and Indian Institutes of Management, were not spared and were multiplied without consideration for infrastructure and faculty. Such competitive strategies did raise the GER to 17%–18%. But that is still far below the world average of 26% and that of other emerging economies such as China (26.7%), Brazil (36%) and Russia (76%). In the context of India's superpower ambition, it is utterly dismal. This gap indicates huge investment and profit opportunity for the global capital.

Irrevocable Consequences

One may cynically think, the private sector's share in higher education in India is already among the highest in the world: 64% of all educational institutions being private. India already allows 100% FDI in education sector, the inflows exceeding $1,171.10 million from April 2000. There are 631 foreign universities/institutions operating in the country, mostly with a concept of "twinning" (joint ventures and academic collaboration with Indian universities), according to the Association of Indian Universities. Historically, higher education in India has been starved of financial support: public expenditure on it being $406 per student, less than even the developing countries like Malaysia ($11,790), Brazil ($3,986), Indonesia ($666) and the Philippines ($625). Quality-wise, higher education in the country is going nowhere; our best institutions rank below 240 in global rankings. So, what more harm can there be if the higher education goes under GATS? The brief answer is that the awkward "for profit" clause in the current policy would go away; all future policies of India in respect of higher education shall be annually reviewed by the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (TPRM), one of WTO's legal instruments and the changes suggested by it shall have to be abided by—an outright infringement on freedom and sovereignty of India—and of course, the reservations and other concessions for Scheduled Castes and the Other Backward Classes, will go. Higher education aimed at producing inert feed for corporate sector shall become a tradeable service which will have to be bought by students as consumers.

Narendra Modi's claims of creating better opportunities for Indian youth get thoroughly exposed when he is set out to shut them out permanently from access to higher education at Nairobi. For the Congress it was expedient, for him it is ideological. The Brahminical supremacist ideology of his Parivar perfectly resonates with social Darwinist neo-liberalism in dispossessing majority of people of whatever little they have and putting a handful of elites to lord over them. For those handfuls, GATS regime in higher education may still mean inexhaustible opportunity but for the multitude of masses it means the death knell. How on earth would they, who are supposed to be subsisting on Rs 20 a day, whose calorie intake has already dipped to a worrisome level, who are in a state of permanent famine, afford the market price for higher education?

Reference

Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) (2011): "Private Sector Participation in Indian Higher Education," FICCI Higher Education Summit.

No comments:

Post a Comment